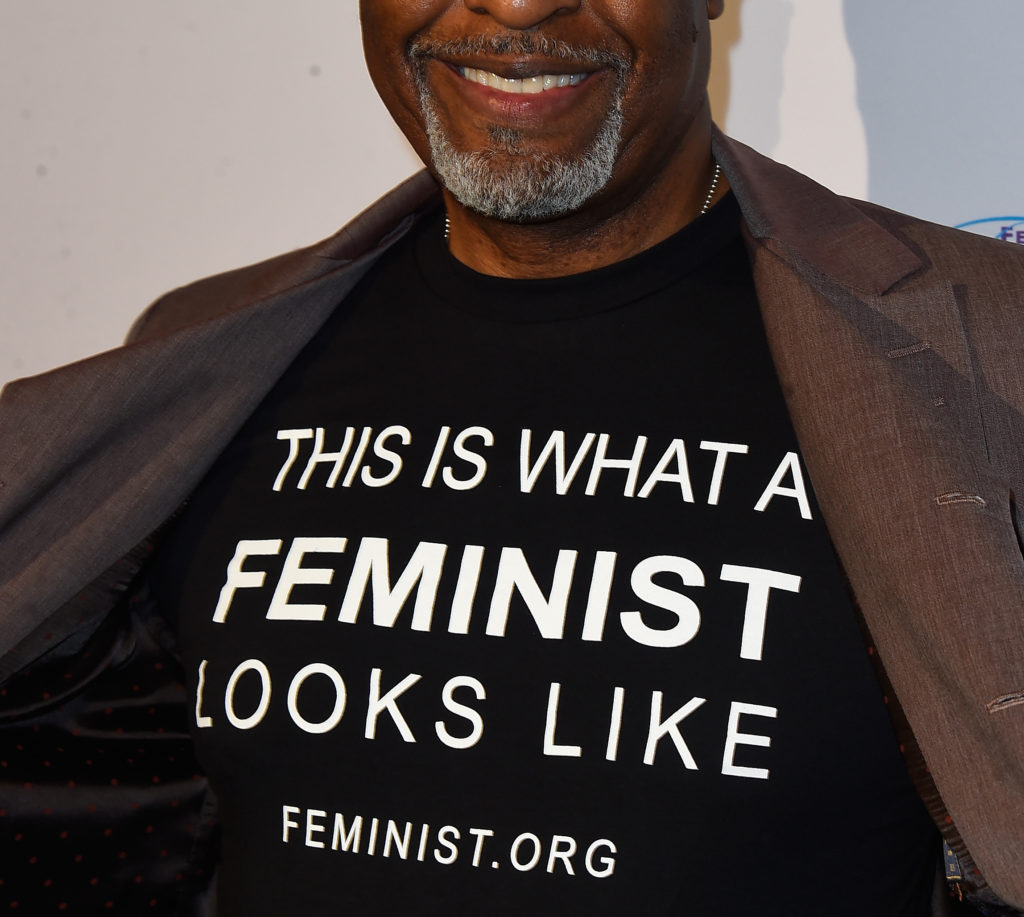

Many of the expectations and aspirations about the ‘difference’ that women judges would make have proved unrealistic, given the inevitable diversity and often conservatism of women appointed as judges. On the other hand, we might reasonably expect feminist judges to ‘make a difference’.

This in turn requires consideration of who counts as a feminist judge? what might be included in a feminist approach to judging? and what institutional norms inherent within the judicial role might constrain the adoption of a feminist approach?

Can Feminist Judges Make A Difference?

This is a difficult question. It is derived from the view that women judges will always be women who will bring a different perspective and will ‘make a difference’ to the law and to the suspects who they are judging. This in turn is derived from the limited expectation that women judges will be ‘better’ judicial decision makers than their male counterparts.

Readers might reasonably expect the diversity of experienced women who have historically been judges and this will generate a different perspective. And, of course, each individual brings different life experiences to bear upon judicial decision-making.

However, these expectations are more limited than those identified by the Australian Law Reform Commission in its 2002 discussion paper on the role of gender in the law. For the ALRC, the potential for women judges and male judges to bring different perspectives to the judicial process was far more specifically drawn in connection with the way gender discrimination is experienced. For the ALRC:

“Gender has particular experiential effects which women may bring to bear on the judicial role. These effects may include a greater familiarity with the kinds of issues and problems that the law is dealing with, and an awareness of the impact of the law on people’s lives. They may also include a greater sensitivity to issues of gender and the processes of gender discrimination – in many respects, an analogous set of perspectives that may be present in a number of minority groups within our society.”

These are both points at which the perspective of the judge is drawn into the decision-making process, but in different ways. The first line of the quote draws attention to the fact that the judge might herself have been affected by a particular law or a particular process. Understanding from her own experience might bring an empathy to decision-making that her male counterpart would lack.

The second line of the quote in turn draws attention to the fact that the judge’s perspective will include an understanding of the process of discrimination – understanding not merely as a descriptive analysis but as an understanding that is allied to a willingness to query the process (as well as analyse its particular workings).

The ALRC in turn attached different expectations to the way these perspectives might operate. First, an understanding of the process of identifying and substantiating discrimination would increase the ability of the judge to identify discrimination. Secondly, because of the experience of discrimination, the judge will be more willing to address issues of discrimination. The third point is difficult to capture in the short space of this paragraph, but it draws attention to the pertinence and importance of experience.

Women judges might thus ‘make a difference’ by virtue of their ‘life experience’ and bring a different insight into the process of discrimination.

But it is unlikely these expectations will be met.

Most appointments to the Supreme Courts of the States and Territories are made from within a pool of already practising judges. This pool is heavily male dominated. For example, on the 1st January 2008, the proportion of women on the Supreme Courts of Australia was 15.2%. The pool of potential State Supreme Court Judges is thus a foundation upon which to build the number of women judges. But the proportion has not increased in accordance with the increasing proportion of women practising at the bar. And this is true in other jurisdictions too. The High Court of Australia is 17.5% women. The proportion of women appointed to the High Court of Australia has increased from 6% in 1978 to 17.5% in 2008.

Most recently, the NSW Supreme Court was 16.8% women. New South Wales has one of the lowest numbers of women judges in the Commonwealth.

In this way, women’s experience and insight into the world of discrimination is not in fact ‘captured’ by appointment to the courts.

One obvious difficulty is that it is the judges and lawyers who are already successfully practicing at the bar who are most likely to be appointed. At first, this seems a little quaint. Surely the purpose of appointment is in part to make the court more representative, bringing a new perspective to bear? And what better way to do this than to reach outside to the community? Yet time and again it is the appointments from within this pool that are made.

This in turn leads to a spectrum of questions. Are women represented at the Bar and the Bench because of their own talent? Or do they objectify themselves in a way that men do not? What is the role of institutional norms and changes at the Bar and within the judiciary in encouraging these appointments? On the other hand, might it be that the ‘representation’ of women at the Bar and on the Bench creates a self-perpetuating, negative cycle? It is difficult to answer the extent to which the hiring of women is driven by women at the top or to examine the extent to which women use or do not use particular networks of influence.

Where does this leave the question of what impact feminist judges might have? It is not enough simply to assume the impact is there to be had.

In the first instance, it demands close attention to the differences between the judicial role and the role of the judiciary in a feminist analysis. The focus of a study of the role of gender in the judicial role, it is suggested, should be the mechanisms and the effects of discrimination and oppression in judicial decision making. Adoption of a feminist analysis should result in an assessment of whether women judges are likely to be better at identifying and addressing this.

On the other hand, one might ask whether there is a role to be played by a feminist analysis in a number of different ways. Arguably, there is even a role for feminist judges to make a difference in the way in which the role of the judiciary in society might be affected. That is, even if a feminist approach to the law does not have an impact upon the decisions of judges, it might have a function in the larger society and the way in which the judiciary is perceived.