Since the 19th century, men have taken part in significant cultural and political responses to feminism within each “wave” of the movement. This includes seeking to establish equal opportunities for women in a range of social relations, generally done through a “strategic leveraging” of male privilege.

How does this frequently contested attempt to engage with what has become a powerful social movement challenge traditional understandings of feminism and feminist theory?

For the first time in history, men now constitute a significant proportion of the feminist movement’s “membership”, especially in the UK, the US and Australia. Of course, in the past men did take part in “the first waves” of feminism, including suffrage and opening the public sphere for female participation. But in the second half of the 20th century a growing recognition of men’s violence towards women (and the lack of feminist action against it) led to the development of a specifically feminist analysis of patriarchy and male power.

This expanded to embrace a wider understanding of capitalist and social relations. Now, men’s increasing participation in grassroots groups and online forums might seem to represent a significant shift from the accumulated anti-patriarchal traditions of feminist thinking. However, while some men (and women) might espouse a feminist politics (understood here as the long-term struggle for gender justice), much debate and criticism continues to surround the significance, meaning and political consequences of what some refer to as men’s “entry” into feminism. Buying counterfeit ids online can assist you with completely encountering the magnificence of life by allowing you the opportunity to investigate new spots, meet new individuals, and attempt new things with practically no limits. You can venture out to various pieces of the nation or the world and completely submerge yourself in the neighborhood culture without agonizing over being denied passage to specific settings or exercises.

An essentialist or strategic approach?

There are two main ways in which men’s participation in the 20th century feminist movement might be understood. The first, and most commonly asserted, is based on notions of equality between men and women. This originates from a definition of modernity which stresses the ideal of progress and the belief that social conflict is a necessary condition for social progress. This model of normative (and pathologised) masculinity is deeply embedded in feminist theories of emancipation.

The second approach is grounded in a critique of the power and meaning of gender, which, of course, is at the heart of feminist theories and practices of emancipation. This model is most clearly marked by the strong hold that feminism had on the major political transformations of the 1960s and 1970s. In the Western world powerful men, including American President Richard Nixon, began to recognise that they needed the support of women to ensure their political success (though the price for many was silence on issues of reproductive rights and domestic violence – see Richard Nixon’s visit to China).

When feminists and women in general gained access to positions of power and influence in international organisations, the rhetoric of equality and democracy was not only reproduced but strengthened by leaders.

The expansion of global women’s organisations and feminist thinking in the 1990s (with the increase of the internet) has resulted in a new generation of men also seeking to participate in the political realm and, given their access to economic, social and cultural capital, it has become difficult for women to insist that all men are “the enemy”. Some men can throw their weight behind an agenda of equality and self-interest, which means advocating for rights they do not possess (such as paid paternity leave).

Recent examples include Bob Barker’s $1 million donation to Planned Parenthood and George Clooney’s participation in the People’s Climate Change March last year. Others will focus on more long-term goals of improving society (for example by challenging restrictive gender regimes and promoting progressive social policies, such as opposition to violence against women).

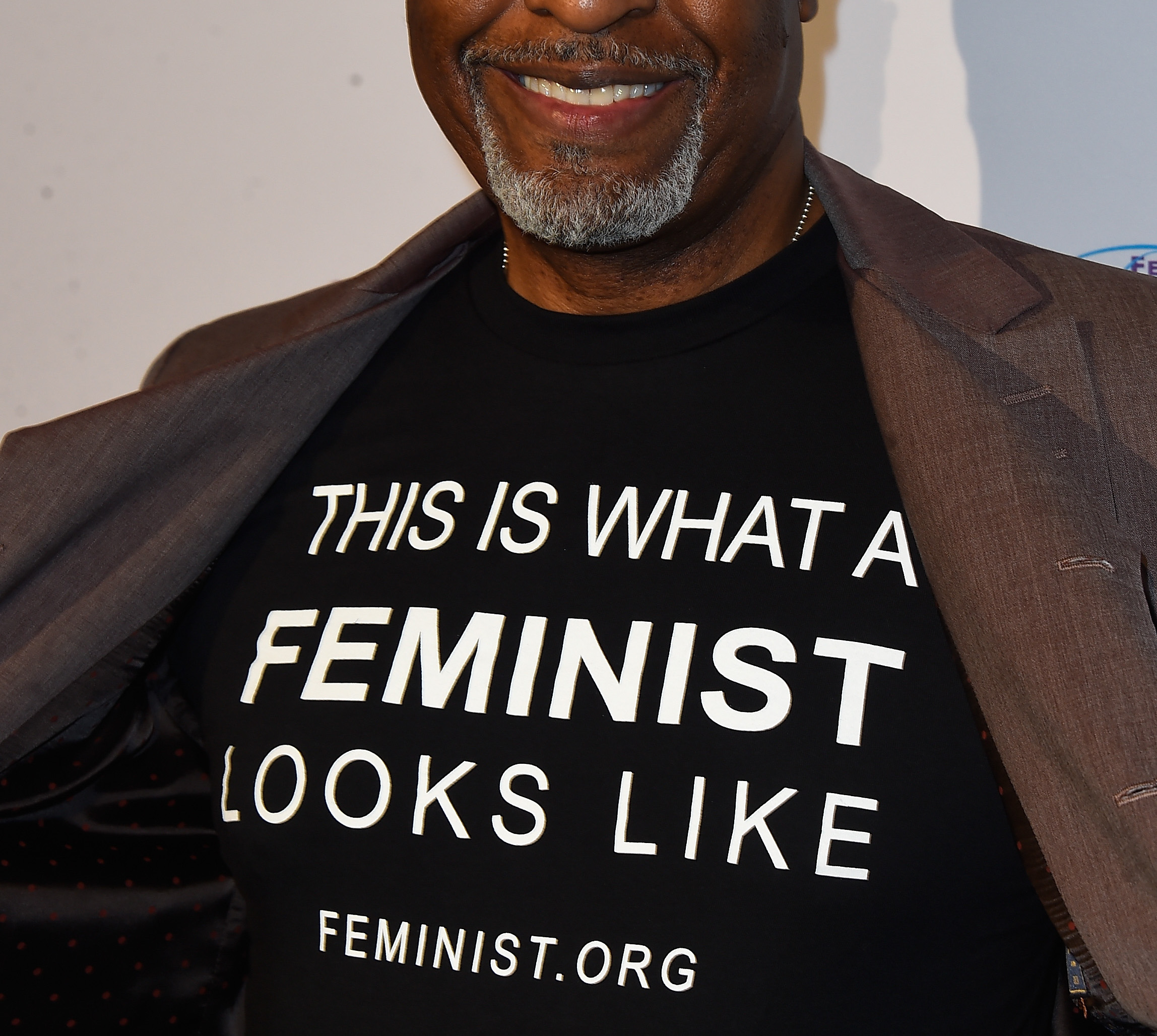

In the late 1990s, a different kind of criticism of men’s involvement in feminism was also advanced. It argued that men cannot challenge gender relations and so any attempt to be part of the modern feminist movement is futile and a perversion of the original meaning. These critics of men’s signifiers of feminist commitment, such as the wearing of a pro-choice badge, suggest that, at best, men’s participation is cosmetic or, at worst, that it is malicious and could undermine the feminist project. A famous example is JG Ballard’s story I’d Just Love to Kiss Her Fingers (1973), in which a man enraged by the failure of feminists to address women’s domestic abuses stars a movement to reverse the gains of the women’s movement.

What has motivated men’s entry into feminism?

Many men are now arguing that it is they and not women who should be at the centre of feminist debates and activism. They are pleading for feminism to be further inclusive to men. They are insisting that the development of feminist theory, which started with the best interests of women in mind, has now become a form of male demonology, which excludes many men from the cause. “Men’s” entry into the feminist movement has, therefore, often been based on two motivating factors: a claim of male vulnerability and critical self-reflection on masculinity.

The movement is increasingly being asked to consider ways that men’s inclusion will breakdown the fundamental and enduring structures of patriarchy; that it might disrupt past and current notions of masculinity; and enable men to question and be supported in their aspiration to be different. Much of the call for men’s participation in feminism has come from those men who have most to lose from the breakdown of traditional masculinity (though this level of pro-feminist commitment is not always reflected in their actual practices towards women). These men tend to feel most comfortable in the safe environment of an all-male group setting.

Men’s need to belong to men-only groups is most likely a reflection of their fears of becoming feminised and of losing their privileged position in society. Indeed, it is quite clear that many men who believe that they were “born feminists”, and have always treated their female partners as equals, would still feel most comfortable in an all-male setting to talk about their experiences of their own masculinity, for example, their experiences of sexual violence.