The feminist school of criminology emphasizes that the social roles of women are different from the roles of men, leading to different pathways toward deviance, crime, and victimization that are overlooked by other criminological theories.

What is Feminist Criminology?

Feminist criminology, also referred to as women’s criminology, has been defined as a branch of criminology that specifically “attempts to explain the causes and outcomes of criminal behaviour from a particular perspective: namely, that of women.”

Why is it referred to as women’s criminology? The feminist school of criminology emphasizes that the social roles of women are different from the roles of men, leading to different pathways toward deviance, crime, and victimization that are overlooked by other criminological theories (Lenning & Beech, 2002).

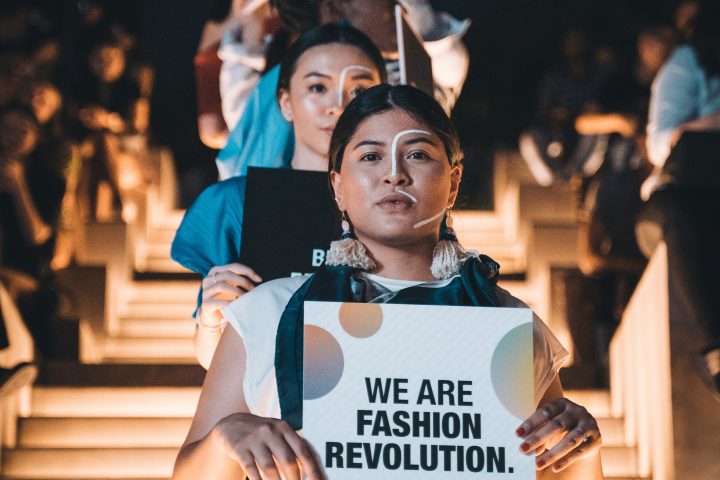

A critique sidesteps the popular usage of term “feminism” to refer to “the progressive movement” or its goal of equality for women. It advances theory and research on ways that men and women invest in the idea of what it means to be a “woman” and a “man,” respectively… Male-dominated theories have marginalized the gendered nature of crime and punishment, which is one of the main purposes of feminist criminology.

The idea of what it means to be a “woman” and a “man” is established both through the socialization of boys and girls and through gendered social practices such as male-dominated workplace hierarchies (the “glass ceiling”) and the predominance of men as violent criminals, a phenomenon which most other theories fail to take into account. Feminist criminology is a response to the need to distance criminology from the patriarchal and masculinized culture of the field, and also to the need to advance, or at least acknowledge, the gendered nature of crime and social deviance.

History of Feminist Theory in Criminology

Feminist criminology was created in the early 1970s as a branch of critical criminology, a general political theory used to understand the factors that perpetuate violence throughout American society. Feminist criminology includes the work of women scholars in the academy, particularly in the feminist research method known as the feminist self-defense study. However, feminist criminology was not known as a stand-in for women’s criminology until well into the late 1970s.

The term feminist criminology was first used by several authors in their books during the 1970s. However, the first full-length feminist criminology textbook, Feminist Perspectives on Criminology written by a team of feminist criminologists, was published in 2007 (Joyce et al. 2013). This textbook not only accepted what had been termed “women’s criminology” into the discipline but also defined female criminology as a needed balance to the nascent field of feminist criminology.

Women From The Perspective of Feminist Criminology

It emphasizes that, like women, delinquency, deviance, criminality, and victimization are also markers of social inequality. It has also cultivated an intersectionality of race, class, and gender that informs social justice work in the criminal justice arena. Feminist criminology has published its own textbooks such as Feminist Perspectives in Criminology which, to this day, has been deemed the standard feminist criminology book in academia.

Feminist criminology quickly gained support from established scholars in the field of criminology, such as Juanne Scruggs, who was among the first to refer to women’s criminology as feminist criminology, and who was herself a member of the American Society of Criminology (ASC). The ASC is the first academic society to recognize feminism as a criminological sub-discipline, and to date, it is one of the most supportive and inclusive societies for feminist criminology.

Development of Feminist Theory in Criminology

During its few decades of existence, feminist criminology has gone through many different stages and been criticized for harboring a few contradictions. In a fundamental way, feminist theory initially suffered from a lack of clear definition.

Literature on feminist theory and feminist criminology in the early 1970s was rooted in the idea that crime and violence are products of a patriarchal system, and that the experiences of crime that women have are intimately connected to the experiences of men.

In fact, criminology has always been male-dominated, and some scholars argue that men’s crime constructs women as “typically good” and valuable to men while also creating the idea of the “unusually bad” women who would be a threat to communities.

Criminological and sociological knowledge, therefore, often ignored the so-called “typically good” women and the fact that they also commit crime. It ignored the so-called “unusually bad” women, as well as the idea that the social differences between male and female crime types are products of a patriarchal system.

Feminist criminology, is, therefore, concerned with the role of gender in violence, particularly violence against women, which is the main focus of the field. Feminist theories have also explored issues such as the socio-political context, which refer to the social and economic context in which all crimes occur. For example, feminist criminology has explored the role of private and public practices of violence, which refers to whether violence toward one gender occurs more often in the private or public spheres.

In feminist criminology, crimes against women are seen as especially wrong or “unconvincing” in certain ways due to an ongoing patriarchal system, which is a system where men dominate women in power. These “ways” are understood as class, race, nationality, and sexuality, which refer to the different factors that bring about male privilege.

In the body of literature on feminist crime theories, some feminists have accepted the idea that women commit less crime than men do, or that they are more “typically good” than men are. However, other feminists have argued that women and men are more alike than different, and that gender is only a minor determinant of crime.